Pruning the brain:

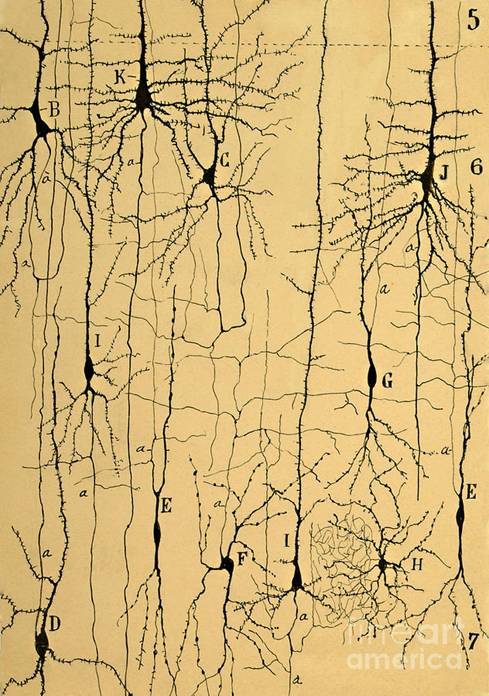

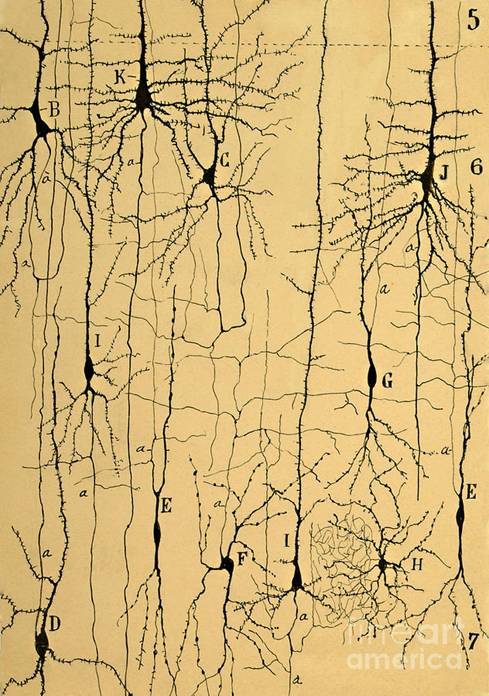

The brain is complex. You can look up the number of neurons; there are other cells that are also important. The neurons are the most fun. Here is a drawing of the dendrites some time after 1887 by Santiago Ramón y Cajal. For years I thought he was two people, a Ramón and a Cajal. The first drawing is the branching system of dendrites of some neurons:

https://www.google.com/search?site=&tbm=isch&source=hp&biw=1241&bih=652&q=cajal+drawings&oq=cajal&gs_l=img.1.4.0l10.3733.4580.0.9722.5.5.0.0.0.0.120.471.4j1.5.0....0...1ac.1.64.img..0.5.465.tOfMqk0qVBk#imgrc=ZbEySp_n0hEbDM%3A downloaded 1/30/16.

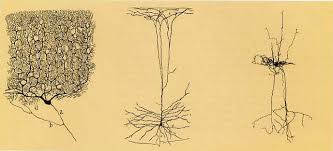

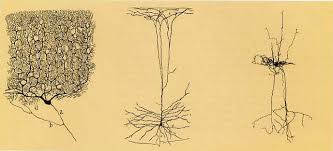

You can recognize the bodies of the neurons; they are the lumps. Each has a branching system of dendrites that together send signals in to the cell bodies. Thence they go out the long axon:

https://www.google.com/search?site=&tbm=isch&source=hp&biw=1241&bih=652&q=cajal+drawings&oq=cajal&gs_l=img.1.4.0l10.3733.4580.0.9722.5.5.0.0.0.0.120.471.4j1.5.0....0...1ac.1.64.img..0.5.465.tOfMqk0qVBk#tbm=isch&q=cajal+drawings+axons+ downloaded 1/30/16 16

There is more branching. Where an axon reaches a dendrite there is a synapse. Think of it as a switch. A single neuron can be connected to a large number of others both upstream and down. The neuron may have a resting rate of firing, of sending a signal down the axon; this signal is all-or-nothing; then there is a latent period during which the neuron will not fire. During and after that time, the neuron collects information from the dendrite, which may be stimulating or suppressing, and when a threshold is reached the neuron fire, unless it has done so according to its basal rate.

The axon and dendrite do not touch nor is the signal passed directly into the receiving neuron. A chemical transmitter is released by the axon, and most of it is rapidly taken back up. The transmitter alters the dendrite on the opposite side of the gap, the synapse.

This all used to make perfectly good sense to me until one day when I was in medical school and was being most kindly kept as a guest at the Institute of Ophthalmology in London my host, Professor Norman Ashton, mentioned an object that stood at the entry way to the institute.

I knew it well, passing by each day I entered. It was rather columnar, a bit taller than I, white with a moderately undulating in a moderately uneven way surface with hundreds of black dots on it, each with an indication that it was hooked up to something. The professor remarked that it was a model of a single synapse.

I may have got his words wrong, but from that day I have regarded the brain as an unfathomably complex thing.

Then there was an article in Nature, which I passed by with little notice, but fortunately it was reviewed. (Brain Gains, Economist vol. 418 no. 8974 January 30, 2016 page 73) The astute science journalist picked up on what I had breezed by. During adolescence and for a while thereafter the brain undergoes a simplification. Synapses, indeed entire neurons are specifically removed en mass. Generally it is thought that little used neurons are eliminated, a few neurons appear, and the resulting potential space is given over to myelination, which means myelin is wrapped around the neurons; I think of it as sort of insulation, but instead of shielding the signal against leak it speeds the signal up, like a thousand fold and more.

So the child is wonderfully plastic, able to adapt to any of a variety of environments even if reared in a foster home. But then it gets sot in its ways and winds up pretty much as a model of the natural parents.

What is new is that that pruning process goes too far in schizophrenia, a devastating emotional condition fraught with hallucinations, delusions and a loss of reality testing. I might add stereotyped behavior but am no expert in the field. But it does ring a bell. I had occasion to witness an interview between a schizophrenic woman and a psychiatry resident. The woman mentioned the presence of somebody. Upon being asked, she said a man was standing at the window. That was not possible; although the window was not too far above the level of the sidewalk there was a sunk heating vent, maybe four feet deep and guarded by a cinderblock wall, just below the window. There was no place to stand there.

Even knowing about the vent I glanced at the window, which was partially obscured but not to much so as to prevent a person from ruling out an observer. The woman could describe the man and what he was doing – which is quite irrelevant for us but which was on keen interest to the doctor – and what his emotional state was. But not once did she make any gesture toward looking out the window where this imaginary and rather disturbing figure was said to be.

She did not show any impulse to reality testing. Actually collecting information was something she did little of. If she had a shortfall in available neurons or at least synapses, that makes a kind of sense.

Then here’s the best bit; there is a condition called autism. I had thought of it as early onset schizophrenia. If an elderly person stops making sense, I have generally found it to be caused by some specific disease; the brain is, or has been normal. The largest number of schizophrenics is said to turn up in teenagers. They were sound enough to endure childhood, but the throes of adolescence were too much. And then those who couldn’t even manage childhood had poor ability to form emotional connections and were uninterested in anything save sometimes one field, in which they might excel.

I was wrong. It turns out that current thinking says that schizophrenics have a runaway pruning process, but autism is associated with insufficient pruning. It still doesn’t quite all jibe for me. They should be fine during the years when the pruning hasn’t set in yet. So don’t turn to me for clarification or advice.

My reaction is that I want my neurons back. I’ll give up my bunny rabbit speed. It’s not much use when the only exercise I’ve had in many years has been monotonously repetitious. I can spend hours, nay as it turns out years, bedeviling a single question. But then I rather like having friends, so maybe I’m just close enough to being autistic to have focus but not too close to have friends.

And I suppose I should not think badly of lauded experts who just don’t get it. They haven’t the nerve.

There have been 188 visitors over the past month and YouTube has faithfully recorded my alternate day visits 206 times.

Home page.